I like to stay in the know of the latest fashion trends - even though I don't necessarily adopt them - and lately there was one in particular that caught my attention, called "lived in luxury."1 If you're wondering, it's exactly what it sounds like: clothing items that look like "you've had them for years." So for example a leather jacket, but made to look like it witnessed your first kiss and the birth of your first child. Instead of having that shiny and polished look that most new leather items have, it shows signs of wear that could make onlookers wonder what life stories it could tell, if it could speak.

I was always fascinated by this kind of trend. The "it's new but looks old." Ironically, the trend itself is the opposite. It isn't new. I remember when I was in high school distressed and ripped jeans were the epitome of coolness. I didn't embrace the trend at that time, probably because I didn't see myself as that cool kid.

But as much as I like it, today's article isn't about fashion. Not even trends in general. Instead, I want to share the ideas that took hold of me while thinking about the roots and ramifications of this "old-but-new" style. And perhaps even over-analyzing what seems like just another consumerist ploy.

It made me consider the relationship between things that are versus those that seem to be, and also how time (and money) factor in this equation.

The central question I'm interested in is: why do we (sometimes) want new things that look like they're old, used and kissed by time?

Let's start with the basics. Some things in life can't be bought.2 While some money gurus might push the idea that you can buy time (usually by outsourcing your tasks),3 one thing you can't buy is the passing of time. For some things to happen, you kinda have to wait. A way to bypass this "inconvenience," however, is to purchase new things that masquerade as being old. If you wish your notebook looked like it belonged to a wise sage who poured his most precious teachings onto the page, well, you're in luck. You can buy one for just $24,99.

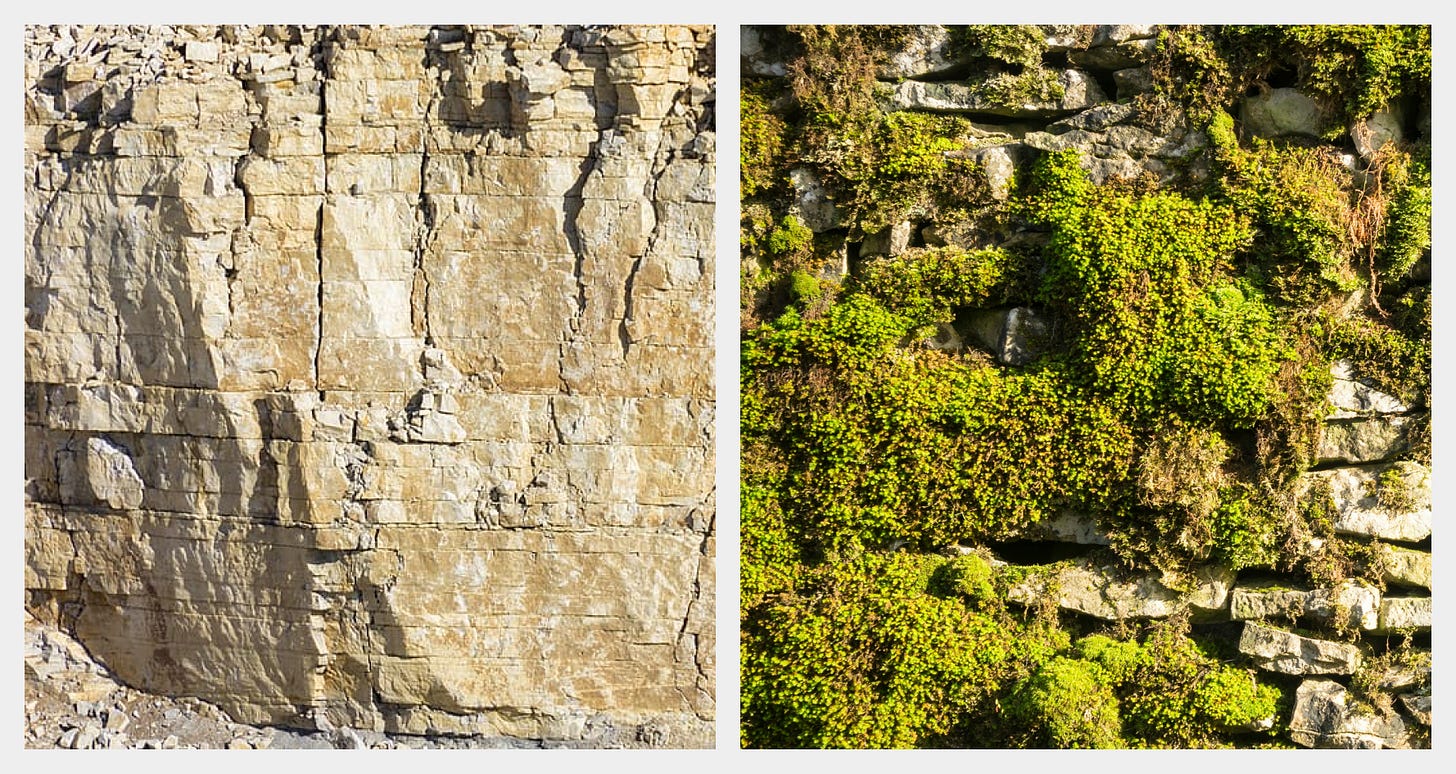

This aesthetic isn't reserved only for personal belongings either. Another place where I came across this desire to "manufacture time" is in Jenny Odell's Saving Time: Discovering a Life Beyond the Clock. In it, she tells the story of Robin Wall Kimmerer, a plant scientist that has been commissioned by a wealthy client to help him transform a wall on his property from a bare, lifeless rockface to a vibrant environment, by covering it in moss.

But there's a catch. The owner wanted the moss to look like it had been there for years. Kimmerer's diagnostic was that the project was impossible, for reasons that had to do with the material conditions of the place: the type of rock, the amount of sunlight, the type of moss. But the owner was adamant to achieve that look, no matter “the cost.”

As Odell observed, the wealthy owner was so used to the logic of "time is money" that he tried to apply it in reverse, wishing to trade money for time. But sometimes nature can't bend to the will of man, no matter how much money you throw at it. Even rich people have to wait for moss to grow.

To go back to my question, a few possible explanations might be that we're fascinated by the marks life leaves after washing over an item. Or the change that occurred. That mysterious patina, which sometimes resembles the wounds of a war soldier. And if we want the look, it's more convenient to get it already "done-for-you," rather than take the time to use that object until it actually is used.

A face with wrinkles may not be as aesthetically pleasing as a youthful one, but it exudes more personality; you can see how time has carved into someone's skin, like a river through a valley. The same is true of everyday objects. Visible signs of wear can endow some items with the grandeur of passed time, which presses upon our mind with all its weight.

Tackling our question from another angle, we could make the banal (but true) observation that we're encouraged to buy new stuff constantly. The rate of turnover for our possessions is high.4 We hardly have time to use them "properly," so we turn to the next best thing: mere representation. With new and exciting things you could be buying, sticking to only one item and truly “wearing it out” isn’t that appealing.

In Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord writes that, "All that once was directly lived has become mere representation." I think there's no better phrase that encapsulated the phenomenon of old-but-new better than this.

Here's more from the book (emphasis my own):

The present stage, in which social life has become completely dominated by the accumulated productions of the economy, is bringing about a general shift from having to appearing—all “having” must now derive its immediate prestige and its ultimate purpose from appearances.

When one buys something that's brand new but looks well-worn, they're buying more than an interesting looking item. It's a trade of money for life in two ways. First, by purchasing it already "used," the person somehow feels like they took the qualities of that piece on themself. All the apparent details of that object get transferred to them. Secondly, in a more tragic way, one eschews the organic process of making an object - be it a notebook, or a mug - their own. They become satisfied with only having, turning away from living.

It's a paradoxical trade. While it may seem that you're injecting your life with character, you're simply applying a coat of "fake time" and call it a day. There's no substance underneath.5

You may argue that no one actually thinks they take on the qualities of their fake old objects, but that's a superficial view. Before you bring anything into you life, you - at least subconsciously - "vet it" in some sense, allowing it to say things about what kind of person you are. Even when you are (or pretend to be) unconcerned about your possessions, that still says something about you, and will inform your choices.

To go back to the wealthy guy and his moss dreams, I think for him it was a case of associating (and maybe rightly so) time with inherent worth. A plant that has grown on a rock and adapted to it, molding itself to that specific environment, is more fascinating than one you planted last week.

Ultimately, as I see it, this trend of old-but-new can be traced back to our fear of death.6 Seeing, in real time, the change and transformation in our possessions - as weeks and years go by, as we use them and contribute to their decay - we're reminded of our own demise. And we can’t deal with that. We’ve got stuff to buy.

I don't know where this leaves us. I don't have a "solution," maybe because I don't think this phenomenon counts as a problem. All I hope is that I gave you some food for thought and perhaps the next time you come across a "fake-old" object, you'll remember to examine it more critically and inquire why (if at all) you're attracted to it.

Thanks to

and for our conversation on this topic.To the disappointment of some.

That almost always implies treating someone else's time as less valuable than yours.

See throw-away society.

I'm aware that this may seem way too dramatic; after all, we're only talking about fake-old objects.

Told you that I was about to overthink this. Nevertheless, I still stand by that assessment.